Growing up, when I found my first friend group that I felt like I really identified with, it was the skateboarders. I don’t remember exactly how I got involved with the crowd I was a part of, but it probably started with Alan. Alan lived right up the road from me in a nice neighborhood with the ideal driveway for all manner of “extreme sports” as they used to be called. These days it’s hard to find a sport you can call extreme; nearly every niche has a fully saturated media presence on Insta or YouTube. Alan’s driveway had a very wide, flat concrete pad at the top, with a nice slope towards a mostly empty street. The next door neighbors had an asphalt driveway if I remember correctly, that created this sort of shallow bowl that was perfect for launching off kickers into or practicing manuals.

This proximity along with the fact that his parents seemed to be very encouraging of his pursuit of skating, made Alan’s driveway the premier skate hangout spot for all the neighborhood kids. If you were into BMX or skateboarding, that was the place to be. Don’t bring those inline skates around though, that was absolutely unconscionable. Inline skates, often conflated with the brand name Rollerblade, had gone through a sort of moment in the late 80’s to early 90’s. Everyone wanted them. They hit a peak sometime around the same era as the Seattle Grunge movement and, as with seemingly all cool things, corporate America tried to capitalize on the craze and ended up completely ruining the cool factor. The once hot new thing had suddenly become synonymous with sanitized, corporate bullshit. They immediately became uncool to a degree that they’re only just now beginning to recover from. If you were a kid around this time, you might remember that “gay” was peak insult and we referred to inline skates as “fruit boots”. If you were LGBTQ growing up around this time, I’m sorry you had to deal with that shit, especially if you heard it from me; I’m glad that at least some of us have grown as people.

Skateboarding just happened to be there at the right place and the right time to fill the void for young rebellious kids of the era. And when we talk about skateboarding, you should probably know that there are several flavors. The one I’m going to be discussing in this piece is street. Of course you had park, which was very rare on the east coast, or vert which was even harder to find. I’m sure longboarders were a thing, but they weren’t popular on the east coast either, especially inland from the surf breaks. You still had some leftover freestylers hanging around on their 80’s style boards but that era had long since given way to what you now probably think of when someone says skateboard: a board with a symmetric upturned nose/tail, usually with some scary graphics on the bottom to keep the Karens of the world on edge, small wheels, and stiff trucks.

Street skateboarding, if it isn’t obvious already, involves skating on obstacles you find “on the streets”. Handrails, ledges, benches, stair sets, anything that presented a challenge or unique opportunity to try something new. If you read my cyberdeck post, you might remember the quick aside where I talked about what it means to be a hacker. I think skaters and hackers are cut from the same cloth in some ways. There is an undercurrent of counter cultural, stick-it-to-the-man attitude that permeates both skate culture and hacker culture. Skaters and hackers both tend to enjoy going places they aren’t supposed to be, often just because they can. While hackers like to find new and creative ways to work with electronics, skate culture is also based heavily on creativity and a similar kind of out of the box thinking. I think this is part of the reason I was drawn to it in the first place.

Things you would probably take for granted as a simple set of stairs, or a curb, or a planter, or a handrail, embody a myriad of different creative ways to express yourself as a skater. One of my favorite modern skaters, Andy Anderson, has such an imaginative style that even things skaters have written off as useless or uninteresting, become a piece of his performative art. His technical prowess is outmatched only by the surprising ways he uses his environment. In the linked video, he goes so far as to put yoga mats and tape on a rail to slow him down enough to skate something that, had you asked me, I would have said was completely unskatable. That’s the dictionary definition of a hack. And that video is chock full of these testaments to creative, non-linear thinking. As the credits roll, he uses the stump of a fallen tree and the broken pieces of sidewalk surrounding it to pull off a ridiculous front side tailslide. This is B-roll footage, and it’s genius. Andy isn’t the GOAT, that title probably will always belong to Rodney, but his contribution to the sport is significant.

I’ve always loved this aspect of the sport. This out of the box, non-linear thinking appealed to me. Skate spots are puzzles to solve. How do you skate this rail that’s so close to the wall? How do you get the speed over this rough patch of concrete? What can you do with this little piece of broken concrete? But also, for a nerdy kid trying to find his place in the world, there was this other aspect of skate culture I didn’t have, but wanted to emulate: the tough as nails, don’t give a fuck, do what you want bravado portrayed by some of the big names of the sport at the time. It wasn’t just an act, either. These people, the professionals, my heroes growing up, were some of the toughest people I could imagine, willing to sacrifice their bodies, break bones and rupture organs, just to go a little bit bigger than ever before. Ryan Sheckler recently released a documentary, Rolling Away where Geoff Rowley, one of the OGs of the skating scene of the early aughts, had this to say:

Why would a professional skater want to continuously smash themselves to pieces to skate a bigger rail, or a bigger gap, bigger everything? Someone’s got to do it. Someone’s got to fuckin’ do it. And the general mainstream sports out there are boring as fuck. – Geoff Rowley

This quote stood out to me for a few reasons. For one, his take on mainstream sports speaks to me. I suppose I can understand why people obsess over teams and rivalries, but I just cannot put myself into that mindset. Nothing about any of the mainstream sports has any appeal. Being a CIS man, people regularly assume this is a safe area of small talk, but my brain immediately enters shutdown mode the moment sportsball comes up in conversation. But more than our shared sense of boredom over traditional sports, I also feel deep in my soul, his mentality that it just has to be done. I imagine George Mallory, stony eyed, staring off into the distance saying “because it’s there”. That’s as good a reason as any, I suppose. And I wanted that. I also wanted to feel invincible. That even if I was smashed to pieces, I was tough enough to get back up and do it again because it’s there, and it needs to be done. That someone was going to be me.

As a kid breaking into his teens, some of this desire I’m sure came from wanting to cut ties with the kid I was and become someone else. I wanted to embody what I thought at the time were quintessential masculine traits: toughness, independence, bravery, maybe a little rebellion. Skating, and skate culture were also edgy, possibly criminal if you got caught skating in the wrong spot. You didn’t conform to the social norms, because that’s not who you really want to be anyway, or maybe you just envy those people and don’t want to admit it. For me it was probably a little of both. It made you part of the in-crowd that was in only because they were out, and in this way it was even more exclusive. Fuck the man. Fuck school. And fuck your popped collar and boat shoes. We’re better than that. We skate. You couldn’t just be born into this clique, you had to prove yourself through dedication and fearlessness.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve kept a small part of who I was back then. Gone are the days when I said I would never work a 9 to 5 in an office; the realities of actually wanting to have money and financial independence pretty quickly ruined that pipe dream for me. My worldview has gotten a lot more nuanced too. I still recoil at the idea of unassailable cultural norms and I loathe the times I’ve had to spend at stuffy, elitist events like the dreaded country club brunch. But I’ve also come to recognize that those things don’t define people in their entirety and that only the worst of the worst deservedly qualify for my lingering teenage angst. I’ve softened on my ideals for masculinity as I’ve become a father and especially as I’ve witnessed injustice in the world first hand. Yes, I still think of strength and grit as being foundational to what it is to be a man, but that can take many forms. It takes courage to express empathy and compassion. It takes real bravery to buck societal norms and stand up for who you are as a person regardless of how you know people will react. And while these forms of courage far exceed that which makes you want to get back up and skate it again, skating did imbue me with a sense that I can conquer my fears and that I could overcome almost anything through sheer will alone.

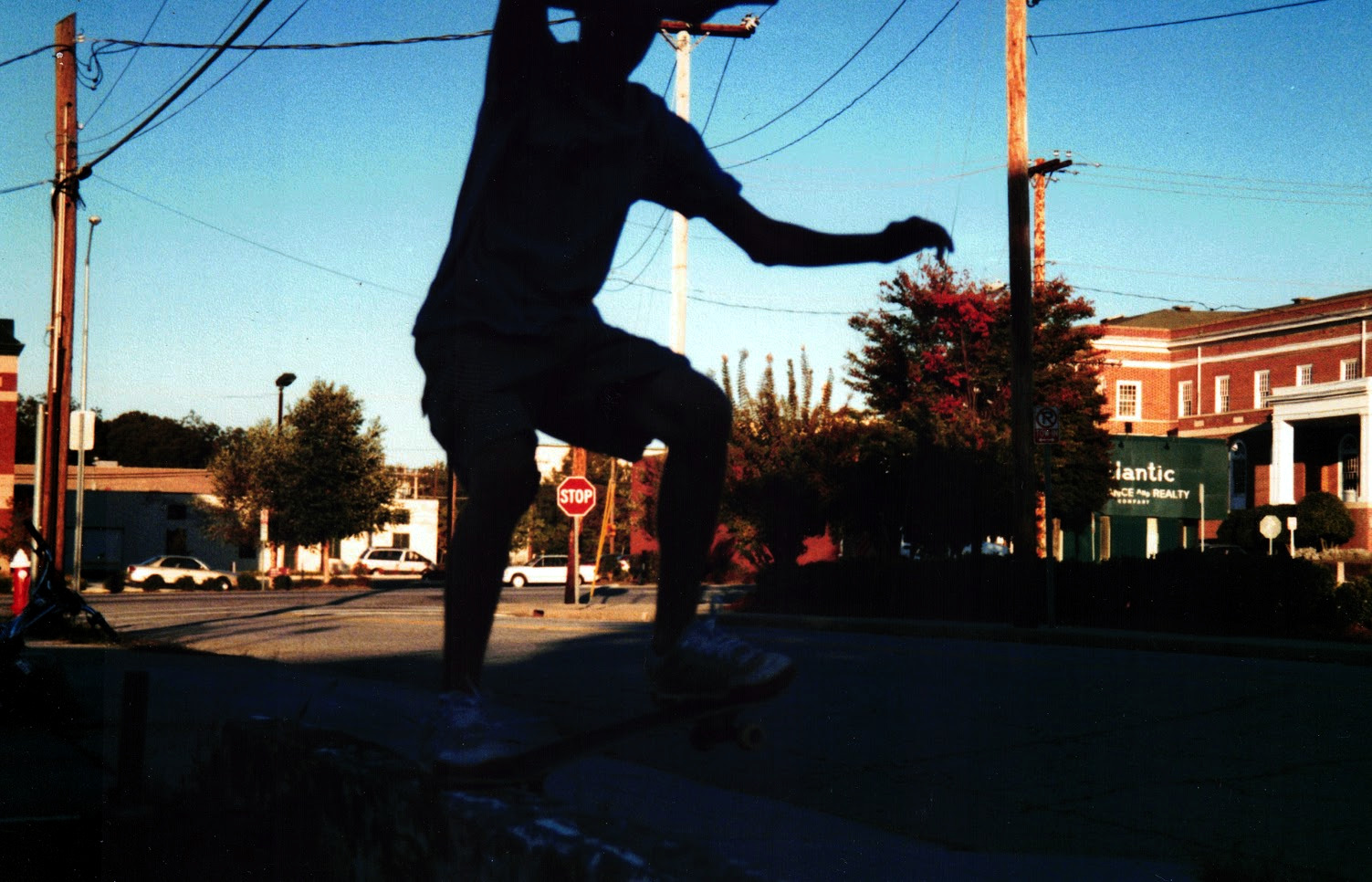

You might notice, if you know me personally, I’m not in any of these pictures. Partly this is because I was the one taking them. I had a Nikon FM10 SLR that I absolutely loved and was sure one day I would make a career out of being a photographer. All the photos in this post were shot on 35mm using this camera, hence the title. I’ve since realized that wasn’t my calling in life. But the other reason I’m not in any of these pictures is because I’ve been lying to you this whole time (well, not lying so much as omitting a very important detail). I don’t skate. Not like these guys did anyway. They were grinding handrails, kickflipping stair sets, and generally making me envious of their skating ability. That’s not to say I can’t skate. I can ollie, I learned to kickflip but I haven’t landed one in years. I had a longboard for quite some time that I would use to bomb hills at ludicrous speeds, but I don’t do that anymore. I mostly kept the wheels on the ground when it came to street skating. I had already chosen my direction in life with my BMX bike and there was no time for me to learn anything else. But I still gravitated towards this group of people because they embodied the type of “I don’t give a single fuck” person I wanted to be. They had broken free from the shackles of parental control. We were listening to Rage Against the Machine and Korn and unless your album had that Parental Advisory warning on it, we weren’t buying it.

I love bikes and I’ve ridden them my whole life. In fact, I’d even say I’m better today than I’ve ever been on a bike skills wise and that’s a fact I’m quite proud of. I started my career on a flatland BMX bike, and although it wasn’t nearly as daring as Jaws on the Lyons 25, I was no stranger to stair sets and hard slams. When we would go out to skate, I would take pictures and document, but I wasn’t just sitting on the sidelines. My old stomping grounds have as many tire marks as chipped concrete and wax stains. These days I’m riding on bigger wheels with knobs and lots of cushy suspension, but deep down, I’ll always have this admiration for street skaters. I still own a board, two actually: a cruiser that I can still ollie and I’ve been trying for that kickflip again, and a surfskate I use to putz around the neighborhood on when I have a few minutes to spare. It still brings me the same joy I felt when I first learned to stand on a board decades ago. I’ve not spoken with anyone in these pictures for years now. The latest I heard Alan was having his first kid. I reached out to him a few years ago as I was going through my old photographs and he told me he and some of the old crew would get together and skate at the local park in K-vegas. We commiserated over old joints and the toll our respective sports have taken on our bodies as we try to stay sharp. I said we should get together again, maybe at the skate park for old time’s sake. But, it never happened.